From 'Tumbleweed Forts: Adventures of an Army Brat'

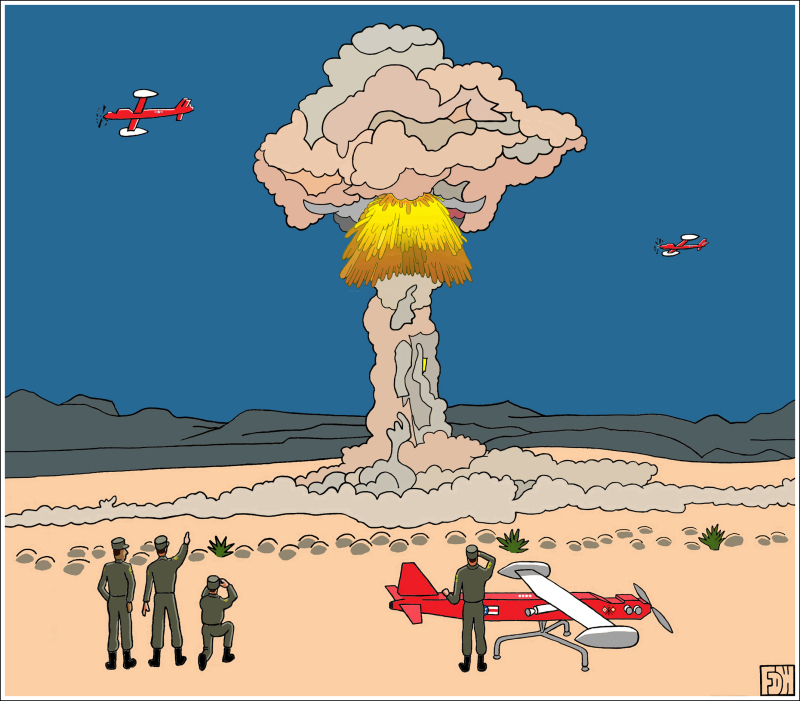

On Christmas Eve, while Dad was painting black roads on his new train set, I asked him for another look at the silver dollars he brought back from the Nevada atomic test.

“I want a closer look," I said. "I might draw a picture of them. You said we could see the silver dollars whenever we wanted.”

“I did say that,” Dad said. He put down the paintbrush and headed down the hall. I hurried after him. My brothers, who knew what I was up to, followed along to Mom and Dad’s bedroom.

Dad opened his closet and pushed his hanging uniforms aside, revealing his 30-30 Marlin, his .22 Winchester and, in front of the rifles, his footlocker.

He opened the footlocker. There was the puzzle box, which he carried to the dining room table.

“This is the Japanese puzzle box your Uncle Carl sent me from Japan in 1951, not long before he was shot down over Korea,” Dad told my brothers and me. “His C-119 cargo plane was based in Japan.

“The box is small, but it’s a pretty safe place to keep things. It’s not easy to open. It doesn’t have a lock, and that’s because the whole box is a lock.”

He turned the box this way and that, shifting the side slats here and there. Then he lifted off the Mount Fuji lid. When he set the box down, we saw the four silver dollars and other mementoes we discovered when Dad was away.

“Here are your silver dollars,” he said, dropping them in my hand.

“That box is neat,” I said, still looking inside. “And what is this?”

I stacked the four coins on the table and pointed to the paper dollar, the real reason I wanted Dad to open the box. I wanted him to tell us about the dollar bill.

“This dollar?” He took it out and stretched it between his hands. “This is something I carried around Europe the last three years of World War II.”

Mom sat down with us.

“Every time my battalion moved to a new location, I’d take the dollar out of my wallet and write down the town’s name,” Dad said.

“Those towns – Harze, Malmedy, Mulartshutte – when were you there?” Carl asked.

“That was December 1944 and January of ’45. We were in Belgium and Germany in the Battle of the Bulge. It was the biggest battle fought by the U.S. Army in World War II.”

“You were in the battle?” I asked.

“Yep. It was that big.”

“What happened there?”

Mom stood up.

“Maybe we don’t need war stories the night before Christmas,” she said. “It’s bedtime, boys. And Tom, don't you have a little town and a big mountain to finish?”

“You’re right, Georgiana,” Dad said. “But let me tell our boys about one night of the war. This was a quiet night, but not really too quiet. It was Christmas 1944, about a week into the big battle. Everyone in my battalion was tired and cold. We stopped at a farm in Belgium, near a village called Harze, and the farmer let a bunch of us sleep that night in the hayloft of his stone barn.

“I was in a sleeping bag, the kind that shut with a long zipper. There were cows on the floor below us. Their body heat helped keep us warm.

“Late that night, the Germans were shooting V-1s, the buzz bombs, over us. They were trying to knock out our supply depots of ammo and gas in Antwerp and Liege. Each one of these little rockets buzzed over like a drone until the engine shut off. Then it dropped, made no noise for five or ten seconds, and boom, it hit the ground and exploded.

“It was funny to listen. In the middle of the night, you could hear all these guys in the hayloft snoring away. But when a V-1 engine went quiet, they’d all stop snoring. And when the bomb blew up, we’d all start snoring again like nothing happened.”

We laughed at Dad’s story. We tried to imagine a chorus of snores interrupted by a bomb, then the snores coming back.

“After the boom, Dad, you felt safe again because the bomb didn’t hit you,” Mark said. “Is that right?”

“That’s right.”

“Did any of the buzz bombs blow up near you?” Mark asked.

“One came close,” Dad said. “It dropped along the road. The explosion knocked over one of our trucks and a trailer, but nobody got hurt. We were lucky that night.”

Mark studied Dad’s old dollar bill. He found the name, Harze. That was where Dad slept under the buzz bombs.

“You know, Dad, sometimes I hear you snore at night,” Mark said.

“What do you think that means?”

“No bombs exploding?”

Dad smiled.

“Yeah, that might be it.”

“Now get to bed, boys,” Mom said. “It’s almost Christmas. Thank God for silent nights.”

As we headed to bed, Dad put the dollar bill back in the puzzle box, and he noticed the four big coins were still on the table.

“Frank, how about these silver dollars?” he called to me. “Didn’t you want to see them?”

“I saw them, thanks,” I said. “I’ll take another look some other day. Merry Christmas, Mom! And Merry Christmas, Sergeant Warner!”

In the morning, Dad’s train set looked like a real town, with houses, shops, lights, and people, and even a church with a steeple. Two locomotives, both puffing smoke, pulled coal cars, freight cars, and passenger cars in and out of the little town.

The mountain was complete. Overnight, it grew hundreds of trees and shrubs, and its tunnels now had stone-trimmed portals to make the openings look more like real tunnels. Dad’s annual miracle was done.

I had asked for a small hand-cranked movie projector for Christmas, and I was so happy to get it. Now I could show old eight-millimeter films of Laurel and Hardy, Betty Boop, and Popeye.

Christmas was one of the few times of the year that Dad joined us for church. Instead of helping us get ready, he put on a civilian suit and walked out the door with us.

Inside Post Chapel No. 1, I studied the little Nativity scene as Father Lustig told us about the birth of Jesus. I thought, look at all these grownups so happy a baby was born.

* * *

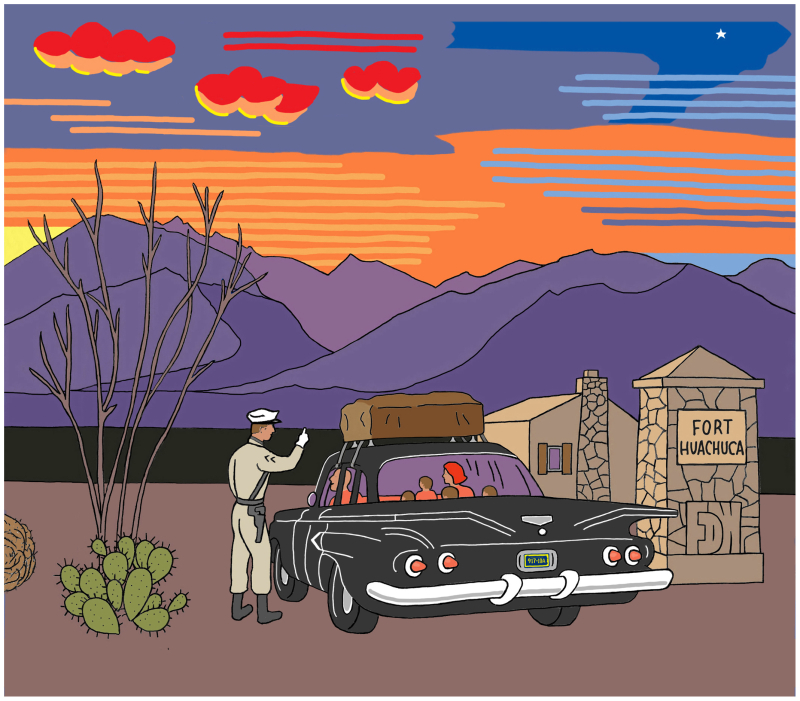

In the photo, from left: George, Mark, Frank and Carl Warner. Fort Huachuca, Arizona, Christmas 1962.